Memory Keeper

Judy Elbaum

It is the day after 9/11—a beautiful autumn day. The air is crystal clear and the sky is flawless azure. I am sitting in the courtyard in back of my house. I spot a blue jay as it flits from the red brick courtyard wall to a nearby yew bush. I see a chipmunk scurry along the ground searching for a burrow. I hear the distinct chirping of a cardinal.

This moment in my courtyard on the day after 9/11 is etched in my mind. I am despondent. We kept saying never again, never again. But how many wars and genocides have occurred since the Holocaust? Bangladesh, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda—tip of the iceberg.

I am repulsed by the never-ending manifestations of evil in this world. For the first time since I gave birth to my children, I question having brought them into this world. Why was I even born?

I am Judy Urman Elbaum, the only child of Holocaust survivors. The name I was given at birth—the one that appears officially on my birth certificate is Marion Judy Urman. Marion is in memory of my maternal grandmother, Miriam, who perished in the Holocaust. Judy is in memory of my paternal grandmother, Yittel, who also perished in the Holocaust. Several weeks after my birth, my father persuaded my mother to call me Judy. He was concerned that there might not be another opportunity for a namesake for his mother. He was the sole survivor of his family and had been an only child. My mother was considered one of the more “fortunate” survivors. Out of her family of nine, five had survived.

My name says it all. I am the heir of a tragic legacy. I am my family’s memory keeper. I must ensure that they are not forgotten and that their stories are told and retold. It’s a heavy burden to bear and it weighs heavily on me. I sometimes find it hard to breathe.

My experience of growing up in the shadow of the Holocaust has been one of extremes, from the depths of despair to the pinnacles of joy. I have many questions. Though I have found some answers, I have come to understand that some questions defy responses, because there are no words to express the incomprehensible.

As a child, I watched my parents grapple with immeasurable loss, all the while progressing with their lives. Every morning at 4:30 a.m., before the crack of dawn, I heard the faint rumble of the garage door rolling open. This was a constant in my years living at home with my parents—from my childhood through my departure for college.

My dad was leaving for work. He never missed a day in all my coming-of-age years. He was steadfast, reliable, determined. He was never really ill. If he did catch a cold, his remedy was a glass of hot tea with a squirt of lemon and a shot of vodka. He was better the next day. I didn’t know it then, but he was my hero.

In the throes of my pre-teen and teen years—I’m ashamed to admit—my parents embarrassed me. Their English bore a heavy Eastern European Jewish accent—so unlike the perfect English spoken by my friends’ parents. We certainly were not like the families on the TV sitcoms of the time—”Leave it to Beaver” and “Father Knows Best.” My parents, especially my mom, were overprotective. If I was late getting home, my mom, much to my mortification, would call all my close friends to try to track me down.

But, at the same time I was experiencing these feelings of annoyance and embarrassment, I couldn’t help but admire my father’s ethic of hard work, endurance, and never giving up. After his brutal incarceration at Auschwitz and the catastrophic loss of his family in the Holocaust, he immigrated to the United States with barely a penny in his pocket and only an eighth-grade education. In spite of what seemed like insurmountable odds, he founded a successful wholesale meat business.

I internalized his work ethic and applied it to my studies. That served the dual purpose of learning good values from my dad, and ensuring that I brought some happiness and pride to my parents. I was their only child, their only hope, and they lived vicariously through me. My hard work paid off. I graduated salutatorian of my high school class. It was a milestone day for me, but what I remember most about my high school graduation was the look of pride in my father’s eyes.

I observed my mom as well. She struggled more with the evil that befell her and her family; she suffered from bouts of depression. And yet, when it came to me, she managed to surface from those dark places. She was the quintessential Jewish mother. When I was little, she sang Yiddish lullabies to me when I was sick or frightened. She nursed me through my childhood illnesses. She fed me endless bowls of chicken soup, placed cold compresses on my fevered brow and hovered over me like a guardian angel, nursing me back to health. She was always there for me, whether it was to place a band-aid on a skinned knee or to listen to me vent about a problem. I was the most fortunate of children to be so loved and cared for by my parents in spite of all that had happened to them, and I knew it.

Unlike my dad, who was unable to salvage any family mementos prior to the war, my mom’s surviving family had managed to rescue some photos. I was intrigued with these photos of my mom with her family before the war. At least I knew what my maternal grandparents and aunts looked like. There is one photo in particular that gave me pause. It’s a photo of my aunt in a very old brown and beige frayed leather photo album. She is my mom’s older sister, Pesl. The photo is faded black and white. She is in what looks like a field of thick foliage. She looks serious, and there is an otherworldly beauty about her.

Pesl was in her early twenties at the time this photo was taken—about a year before the war broke out in Poland in 1939. She could have gone to a forced labor camp, but chose to remain with her parents and eight-years old baby sister, Zlatka. I am haunted by this photo.

My mother tells me that Pesl was a poet who loved literature and writing. She had a kind heart and was devoted to her family. I often look at her photo in silence and lament not knowing her. I was deprived of a relationship with this special woman. In its place are silent imaginary exchanges. I sometimes wonder what it would be like to converse with Aunt Pesl. What was her life like before the war? What books did she read? Could she recommend one to me? Could she share one of her poems? Pesl’s short life of beauty and devotion lives on in my memory as a blessing to me.

Pesl, Circa 1938

My grandparents also abide in me. I may not know what my paternal grandparents looked like, but I’ve kept them alive in my mind’s eye along with my maternal grandparents and my aunts. That whole grandparent/grandchild thing or lack thereof loomed large in my life. Whenever there were gatherings of my parents’ fellow Holocaust survivors, there were never any senior citizens around. The Holocaust created a whole demographic of baby boomers without grandparents. I was one of many of the second generation who never knew what it was to have a grandparent.

The Rosmarins, circa 1942: Top Row left to right: Uncle Chunek, Aunt Pesl, Uncle Heindel, Fela (my mom); bottom row left to right: Grandmother Miriam, Aunt Zlatka, Grandfather Yaakov. My mom and her four brothers survived, (two not shown here). My grandparents and two aunts perished in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

One thing was for sure: The universe had to fill this void in our lives. My parents would be grandparents. My children would belong to and benefit from that grandparent/grandchild mutual admiration society. Ich vill einiklech, my dad would say (Yiddish for “I want grandchildren”). To me, that meant work hard in college, but not too hard. Find work after graduation that won’t be too demanding, and make sure your office is not too far from home. You need to focus on finding the right nice Jewish boy to help you start a family.

My parents were not going to leave my love life to chance. They intervened and set me up on a blind date with the son of family friends. I was not a fan of blind dates, but I was pleasantly surprised. My future husband, Steve, and I bonded over our mutual appreciation of French cuisine and that “aha” moment when the second generation meet and have an instant connection and understanding about what life was like growing up as the children of Holocaust survivors.

My husband, Steve, with his parents, Sala Bierman Elbaum and Izak Elbaum, in a Displaced Persons Settlement, Nabburg, Germany, 1949.

As I revisit this part of my young adult life, I realize that my parents’ wishes influenced my college course choices, the work I chose upon graduation, and my choice of spouse and decision to start a family soon after marrying. Surprisingly, I was not really resentful of my parents for getting so involved in my life. It’s hard for me to separate what they wanted from what I wanted. My marriage was and is a happy one, and having children has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

My Dad, David Urman, of blessed memory, with his first grandchild, Lawrence, 1982.

It has not been pain-free, however. In December of 1984, my husband and I were expecting our second child. He was born very prematurely at only twenty-five weeks gestation and weighed a little over one pound. We named him Saul after Steve’s mother, Sala, a Holocaust survivor who passed away a year before our wedding. My sweet little boy only lived three days. It was not meant to be.

How do you make sense of such a loss? I had watched how my parents did it. I saw my mother’s commitment to anchor our family in a humble, warm and comforting place to call home. I saw my dad’s constancy, fortitude and perseverance as he built a new life in his beloved America. In spite of all they had endured, my mom and dad forged ahead with faith, love, optimism and gratitude. I observed, I learned and I absorbed their ways of being. When baby Saul died, I knew what I would do.

There were times when it was hard to get out of bed in the morning. But I learned from my parents how to grieve. Somehow, I got through it—I survived. And then I carried on and tried to distill some goodness from the sadness. I became a volunteer for the ARC at Stepping Stones in Livingston, New Jersey—a program of early intervention and a preschool for special needs children, many of whom have Down Syndrome. I volunteered there for over fifteen years, and I edited a book for them entitled The ARC Family Diaries. It was a heartwarming compilation of essays, poems, photos and artwork submitted by parents, grandparents, siblings, staff, volunteers and the special needs children. It was my way of being with baby Saul and keeping his memory alive. I was a memory keeper after all.

Which leads me back to some of the questions I posed early on in this essay.

Why was I born? There could be as many answers to this question as there are days in my life, or no answers at all. If I approach this question from my parents’ perspective, I was born because they believed there was enough good in this world to bring me here and rebuild their lives after all they had gone through. And they wanted to ensure that those we lost would not be forgotten.

Why did I have children? How could I not? If my parents could take that leap of faith, how could I not? The einiklech (grandchildren) that my parents so desperately wanted would bring them happiness and pride and affirm the continuity of their descendants, their culture and their traditions.

Why is it that I sometimes find it hard to breathe? Perhaps another question I’d like to ask Aunt Pesl, but dare not, is how did they die? When I have trouble breathing, am I reliving the final moments of my loved ones? Perhaps, I can breathe a little easier now that I have it down on paper.

As for the questions that defy answers, there are images. When I think about my G2 experience, an image prevails. It is an image reported to me by a dear friend who attended my wedding. She was struck by the sea of tattooed forearms pumping up and down in jubilation as they lifted my husband and me up on chairs and danced around us to the hora. So much joy and so much sorrow embedded in one image. The heartache is there. It is tattooed on the forearms of the victims as a constant reminder of the horror. That makes the wedding celebration that much more joyful and celebratory. The happiness, the thankfulness, the exuberance are all there, and they are palpable. How miraculous for the survivors to have made it to this wedding in spite of it all!

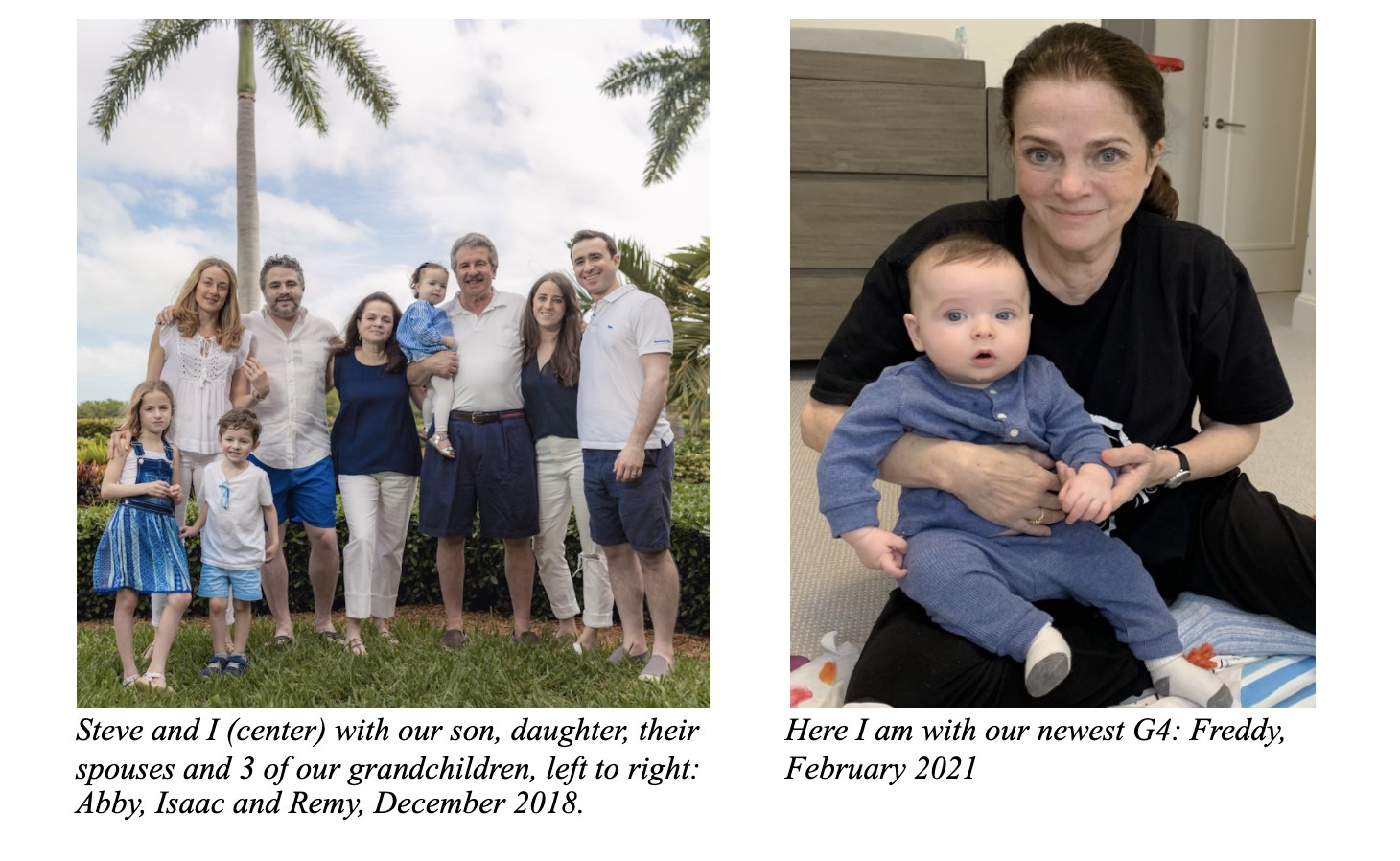

The Auschwitz number on my dad’s forearm is tattooed across my heart and seared into my soul as a permanent marker of the atrocities my family suffered in the Holocaust. But that hasn’t stopped me from living my best life. I am the matriarch of a thriving family—a son, a daughter, their spouses and four precious grandchildren. They are contributing members of society and have made this world a better place in which to live. When I’m no longer here, they will assume my role as family memory keeper and pass it on to their children. The lives of those we lost will never be forgotten. We will honor our sacred calling from generation to generation. If only they could see us now. How proud they would be!